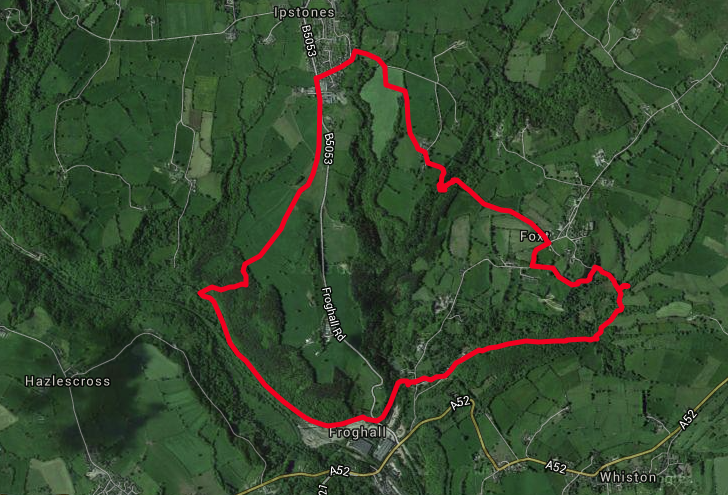

This 5 mile walk commences with a sedate journey along the Caldon Canal from Froghall before rising out of the valley through lush woodland. Breathe in wonderful views before concluding with a walk down what is claimed to be the oldest official railway in the world.

It’s a May weekend and I’m staying at Foxtwood Cottages in return for writing this trail for the Discover Derbyshire & Peak District app. It’s the second time this year we’ve come to such an arrangement with an accommodation provider.

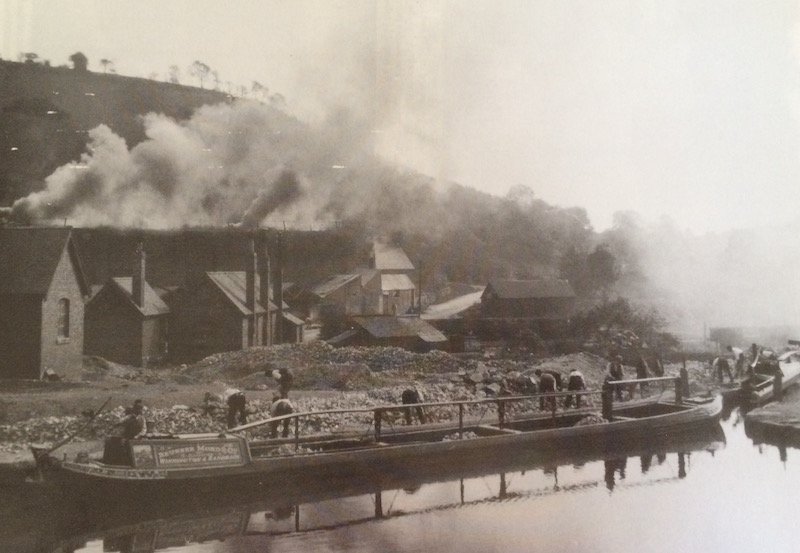

Today Froghall Wharf is a quintessential idyllic rural location, but in every corner lies evidence of a once bustling hub of industry.

Imagine the scene here in the 19th century. Small trucks laden with limestone would have continuously arrived down the incline from Caldon Low Quarry, three miles to the east. Loads were shunted around the yard to be processed; some transported straight onto the waiting canal boats and railway trucks, whilst gangs of men crushed yet more limestone and fed it into the imposing bank of limekilns that now stand guard over the car park.

At the height of production, it is said that one boat arrived every ten minutes to be loaded by hand with 30 tons of limestone, and then distributed across the country.

Alison Worrall’s family have lived in this area for generations. She runs Foxtwood Cottages, standing on the site of Bottoms Brickworks, on the opposite bank of the canal at Froghall Wharf.

Audio: Alison Worrall talks about her family connections to Froghall

Alternating layers of coal and crushed limestone were loaded from the top of the kilns through the ‘charging holes’. A fire was lit in the draw hole at the bottom, which then spread up through the kiln to produce quicklime – yellow when hot but white when cooled.

Lime added to acidic soils improves the fertility of the soil, increasing crop yields. It was also used for lime mortar and in the pottery and iron making process.

It took at least a day to load the kiln, three days to fire it, two days to cool and a day to unload.

The crushing plant would have made a tremendous noise and a toxic veil of acrid smoke would have shrouded this part of the valley during firing.

Across the road from the main car park is Lock 1, the start of the now defunct Uttoxeter Canal and a thirteen mile extension to the Caldon Canal. Today the Churnet Valley Railway runs along most of its length, although isolated watery loops are still evident.

All the paths from here lead to the Caldon Canal. Once on the towpath and you will soon cross Blackbank Brook, one of the tributaries that feeds into the River Churnet. An overflow weir shortly after keeps the canal from flooding. Indeed, the water levels in the canal had to be reduced by 100mm when the canal was restored in 1974 to accommodate larger modern boats navigating the notoriously low Froghall Tunnel (No 54).

I carefully cross the road to rejoin the towpath and the original terminus of the Caldon Canal that opened in 1778. It was another eight years before the canal was extended through the tunnel to Froghall Wharf.

Sandwiched between the canal and the railway, which will become evident shortly, stood the imposing works of Thomas Bolton & Sons Ltd.

The company’s origins can be traced back to the narrow and dark streets of Birmingham in the 1780s. From humble beginnings as metal platers and buckle-makers the company evolved into hardware merchants with an international reputation by the early nineteenth century.

When Thomas Bolton bought a wire and tube mill at nearby Oakamoor in 1852 it set Boltons on the road to becoming one of the leading houses in the copper and brass trade. They provided the copper wire for the first, second and third transatlantic telegraph cables between 1857-66. Communication ‘across the pond’ now took minutes, not days.

The company was also closely associated with the developments of the very first electrical lighting companies, power station development, and in the early aluminium industry. As such, the growth in demand for high conductivity copper was outstripping their existing capacity, so a decision was made to build a new factory in 1890. That location was here at Froghall. But why?

It is widely assumed that the works were built here to take advantage of the increased output from Ecton Mine, but the real reason is the combination of local coal supplies, water power and a location already part of the way towards the metal’s major market in the Birmingham area. Most of its copper came from America and by the late 1920s, Central Africa, arriving at the works by rail.

More recently the company were involved in the generator powering for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, but in 2014 Thomas Bolton & Sons went into administration, a few weeks after an explosion – residents claimed shook their houses and clouds of orange smoke appeared over the site – that knocked two of their three furnaces out of action.

The night before this walk I rode down this stretch of the canal on my bike. As I reached the end of the old works a russet-coloured Tawny owl swooped out from the Thomas Bolton site and into the woods on the right. Now, during my walk, the piercing whistle and rhythmic shunting of a steam engine interrupt the chorus of bird song. Not all of it native. A peacock, or more likely several, are mewing across the valley. The train disappears as quickly as it came into view, leaving me to admire the carpet of Ramsons – wild Garlic – along the path sides. The smell is lovely.

Audio: A mix of native and exotic bird calls in the Churnet Valley during May

After passing beyond the former site of Thomas Bolton & Sons you will see the track of the Churnet Valley Railway down to the left. Last year I interviewed Peter Green from North Staffordshire Railway Company about the history of the railway.

Audio: Peter Green’s history of the Churnet Valley Railway

A few hundred metres further along the towpath is an odd construction. I asked my kids what they thought it was. Somewhere to park the boats? No, the entrance is far too narrow. Further clues were pointed out: the ramp and a question about the narrow boats were powered.

Occasionally a horse would fall into the canal, this ramp enabled them to get out safely. It isn’t an original feature, but one added when the canal was restored and for a short time horse-drawn boats (this time for paying day trip passengers) made a return.

The Caldon Canal, linking Froghall with Etruria on the Trent and Mersey, opened in 1778. Steve Wood was another whom I had previously interviewed. He wears a variety of hats, and as a member of the Inland Waterways Association he knows a thing or two about the Caldon Canal.

Audio: Steve Wood talks about the history of the Caldon Canal

Success was relatively short-lived. The whole network of the Trent & Mersey Canal company was bought out by the North Staffordshire Railway in 1846 and competition from both road and rail proved too much. Over the ensuing one hundred years the canal fell into decline. However, during the 1960s there was enough enthusiasm to restore it. Neil and Cath Price are lifelong boaters who were using the canal even before it officially re-opened in 1974. They, like I, attended the Caldon 40 event at Cheddleton in 2014.

Audio: Neil and Cath Price have boated on the Caldon Canal since it was restored

Since that time the number of boats has increased from 30 per annum to 3000!

Just before reaching Cherry Eye Bridge (No 54) – which refers to the colour of the ironstone miners’ eyes after a day underground in the mines in Ruelow Wood on the north bank of the canal – I reach a milepost. In fact two milestones: a replacement cast iron one, and the original stone one rescued from the waterways museum at Stoke Bruerne where it had languished face down in a shed for years.

Before taking the footpath on the left – littered with waymark discs of varying decay – and crossing over the bridge, I take a closer look at the bridge. It’s unusual peaked shape was said to be a condition set out by the landowner. Rope marks are evident in the archway and the timbers added to protect the stone.

Once across the bridge my course takes me right to traverse the increasingly steep hillside through humid lush woodland. The bluebells may be past their best for this year but the fronds of ferns are in various states of unravelment. Lady’s smock and rushes enjoy the damper areas.

At the summit, the valley sides give way to exposed open pastures. The wind, carrying grey clouds from the south, buffers my ears with bassy tones whilst the grass, still carrying drops of rain deposited last night, turn my boots and trouser bottoms a darker shade of blue.

From the second field Ipstones comes into view; a cluster of buildings riding on the contours of the hillside. Trees and masts of varying types pepper the skyline above, and the second half of the walk is visible to the right.

I pass a picture-book horse chestnut. I say picture book because it reminds me of an illustration that adorned the cover one of my favourite childhood books, the Ladybird book of Trees. No tree epitomises May better than a horse chestnut with those beautiful lantern-like flower arrangements.

After crossing two more fields with indistinct paths – the water has now worked its way through the un-dubbed seams of my boots where damp seeds heads have collected – the 30mph signs announce my arrival in Ipstones. The sycamores hang heavy over the tarmac footpath with their fresh green leaves.

For a small village it has a thriving number of businesses. At its heart you’ll find the Old Red Lion. It was here in 1772 that canal engineer James Brindley (also engineer for the Chesterfield Canal among others) slept in a damp bed after being caught in a rain storm whilst surveying the route of the Caldon Canal. He caught a severe chill and subsequently died of pneumonia.

Ipstones was a working class village for scores of workmen who made their way down to Froghall for work each day. I’m not going there today (I saved that for a Sunday roast the next day) instead it is a right along Brookfields Road, followed by another right into a cul-de-sac to pick up the Byway Open to All Traffic.

At the summit of this narrow lane its a right turn and back onto footpaths. I love OS maps, but they aren’t always updated to include the loss of field boundaries. Let’s just say I went a little wrong and before retracing my steps and picking up the footpath by using the few remaining trees as a guide to the former hedges, I was given a welcome fanfare by two canada geese who swiftly departed before completing two noisy laps of the surrounding fields.

Once through Clough Head Farm its downhill again through more lush woodland. I cross a small stream via the wooden footbridge and work my way uphill criss-crossing the streams and outflows populated by chunks of beige and orange coloured millstone grit. Bluebells and Greater Stitchwort provide extra colour to the gently swaying green leaves and damp earth.

Next I pass through a stone squeeze stile, now superseded by a wooden stile and post and wire fence. The footpath crosses the access track into the field ahead and rejoins it up on the right after approximately 100 metres. In this field to the left are the remains of spoil tips, and in the top left hand corner are lime kilns where locals once burnt lime for use in building and improving the land.

The track takes me to Foxt. I take a short detour to the Fox and Goose in the centre of the village. Opposite this pub are a row of cottages that were said to be stables for the packhorse mules that carried copper from Ecton Mine to Whiston. I’m going to be joining this packhorse route shortly.

Then its down the road to take the first left on a sharp right hand bend in the road to follow the old track. The row of cottages below was built by Thomas Boltons. In 1911 they housed workers who were transferred from a factory in Birmingham. The foreman lived in the larger row of houses over the road.

A natural rock outcrop of red/orange millstone grit stands next to the path. It has been graffitied in chalk with ‘Knock to enter’. I take a step back and it looks like a small cottage with a door. I knock, but no-one answers!

Around the corner a wren dances to safety between the twigs. I take a moment to appreciate the bird song which has almost faded from my conscience. I am beside a ramshackle set of sheds. This is, or was, Fernbank Farm – once a supplier of shetland and wood products.

Over the stile I turn right and begin a toe squashing trudge downhill along the old sunken packhorse route. Immediately after crossing another stile I take a 50 metre detour to the left.

The small and seemingly insignificant wooden post and rail fencing marks a bridge over Shirley Brook. It was constructed in 1777-8 to carry the first wagonway from Caldon Low Quarries to Froghall Wharf, and is thus one of the very first ‘railway’ bridges in the world to exist. There was a lot of infill to create this level crossing point.

I’m not crossing Shirley Brook here, instead I return back to pick up the Moorlands Walk – way mark discs illustrated with a lapwing – and cross over the more modern wooden bridge. There are no lapwing here but I’m soon mobbed by a herd of curious calves along the bottom of the next field.

Safely out of the next field it is up some steps to another surprising find – a small ornate stone tunnel on the left.

This horse tunnel carried the second Caldon Low wagonway (constructed in 1785) below a fourth one (1847) and suggests that the earlier route must still have been in use at this time. These two wagonways followed a similar route down the incline to Froghall Wharf, although most evidence of the earlier route has now been lost.

The Caldon Canal, a branch line of the Trent & Mersey, was constructed to export the ‘inexhautable supplies of limestone’ from Caldon Low, a claim that wasn’t too far from the mark. However, the final three miles eastwards from Froghall Wharf to the quarries, which were a further 200 metres above sea level, were just too steep for a waterway.

In 1776 an Act of Parliament authorising the construction of a wagonway (or railway as we now would know it) was passed. This was for the first of the Froghall Plateways, and as such, the first railway in the world to be officially built. It’s primitive double line of flat iron rails fixed on top of wooden wooden rails – the sections fitting together by triangular projection and corresponding notches – caused wagons to slip, particularly in cold and wet weather.

The second line in 1785 followed a gentler sloping route by diverting south around Oldridge, but this too was much like the first in terms of construction; full trucks of stone often overtook the horses that were supposed to be hauling them!

Scottish civil engineer John Rennie designed a third route – a tramroad via Whiston – that took an entirely different approach and utilised lengths of much shallower gradient with steep inclined planes. The double iron track was laid on stone blocks and horses were now only employed for the sections between the steep planes. This 1804 route increased output dramatically, however, wagons had to be uncoupled each time the top of an inclined plane was reached.

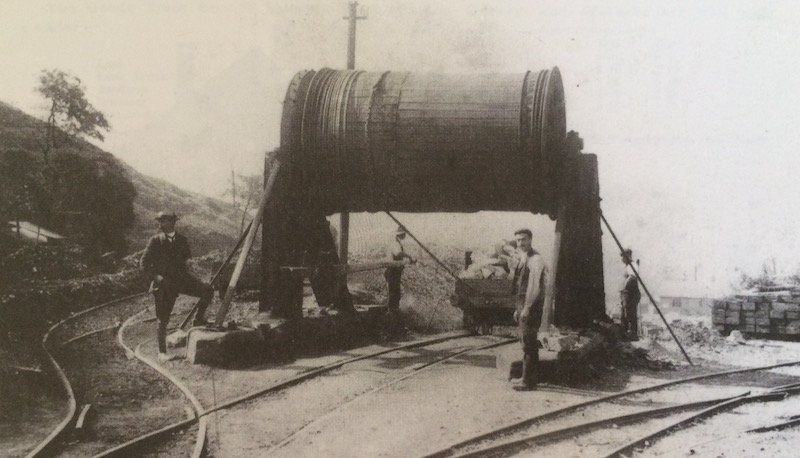

As a result, James Trubshaw devised a 3ft 6in gauge rack railway that utilised the most modern of railway construction methods. It was opened for business in 1847. Blasting through hillsides was now possible, and the continuous gradient, coupled with relative straightness, proved successful right into the twentieth century, when a standard gauge railway was constructed via Leekbrook and Ipstones. Today all five lines are disused.

My walk is almost complete. At the road I turn left. The small open building on the left is the winding house of the 1804 tramroad that ran along what is now the public footpath to Whiston. Gravity carried fully loaded trucks down at the same time as hauling empty ones back up the plane.

I pick up the path on the right to pass between the stone base of one of the huge drums that wound the cable of the 1847 rack railway. From here, branch routes led off to tipplers on top of the lime kilns. I make my way back to Foxtwood Cottages just as the rain, which has been threatening all morning, starts to make its presence felt.

If you run accommodation in the Peak District area and would like us to write a trail for you in return for a couple of nights then get in touch. We’ll add the trail to the Discover Derbyshire & Peak District app. If you are located further afield, contact us to discover what we can do for you.

Thanks to Richard Whiting (Staffordshire Wildlife Trust/Churnet Valley Living Landscape) and Peter Lead’s ‘The Caldon Canal and Tramroads’ book for information about the Caldon Low Railways

Please note: all the recordings on this page were made by Audio Trails, please don’t use without the author’s consent.

1 thought on “A weekend walk in Froghall in the Churnet Valley”

Comments are closed.